One weekend in the fall of 1996, Pam and I flew to Austin to visit the printmaking department at the University of Texas at Austin and do a little sightseeing. The Blanton Museum of Art was open, so we wandered in to check out the exhibition on view. We found ourselves in front of a stunning installation by Radcliffe Bailey which was a large-scale assemblage of painted wood, canvas and photographs. This work commemorates the death of the four children killed in the Birmingham church bombing of 1963. His use of rich colors, the moving topic, and his unusual use of materials made his work mesmerizing and compelling.

Renee Bott, Radcliffe Bailey and Pam Paulson In the Emeryville studio, 1997

Upon returning to Berkeley, we immediately set to work contacting Radcliffe to invite him to come work with us at the press. In 1996, we didn’t have internet or email, so with the help of Betsy Senior Fine Art, a gallery in New York, we were able to extend our invitation to him.

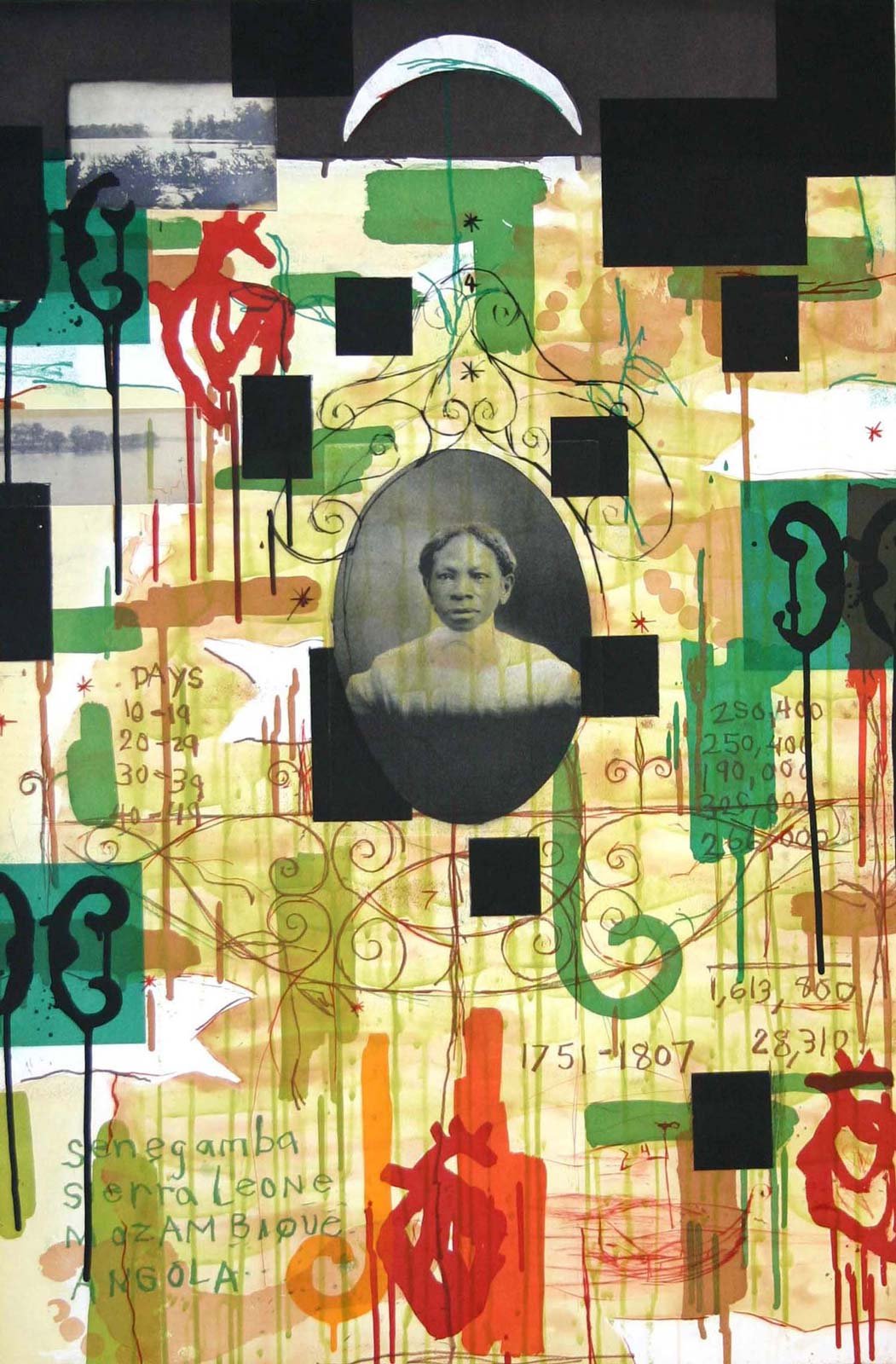

In his paintings, Radcliffe often would use a central photographic portrait of African Americans taken before the turn of the century. He sourced these portraits from local garage sales and church bazaars in and around Atlanta, where he lived. In preparation for his upcoming project, Radcliffe sent us three small tintypes of portraits from the 1800s, which we enlarged and made into photogravures, a photographic procedure that turns a photograph into a copper plate etching.

In the spring of 1997, Radcliffe boarded a plane in Atlanta and flew to Oakland.

Radcliffe was exceptionally shy. He spoke so quietly I had to strain to hear him. Communication was a little awkward and slow at first. But once Radcliffe saw how his marks looked when they were etched and printed, he quickly grasped the basics, and things began to come together. We made four prints on Radcliffe’s project with our press. I remember that, after he made a large spitbite plate, we printed it in blue with the photogravure of a young black man as the central image, glued into the print.

Radcliffe Bailey: UNTIL I DIE/ GEORGIA TRESS IN THE UPPER ROOM, 1997 Color aquatint with photogravure etching and chine collé, 44 1⁄4 x 30 3⁄4”, Edition of 35

Radcliffe stood back and, nodding slightly, he said, “You are going to make my work better.” On another print, Radcliffe wanted to have footprints travel across the print. We asked him how he made footprints in his paintings, and he answered that he just put paint on his feet and walked on the canvas. Adopting his straightforward approach, we mixed up an extra-large batch of sugar lift and painted Radcliffe’s feet with the sticky concoction so that he could walk across the copper plate. You can see his sugar lift aquatint footprints in the print Until I Die: Crossing 1997.

Radcliffe Baiely: UNTIL I DIE/ CROSSING, 1997, Color aquatint with photogravure etching and chine collé, 44 1⁄4 x 30 3⁄4”, Edition of 35

Radcliffe made four beautiful prints with us in 1997. He worked with us several more times, making monoprints from the various stages of working proofs we pulled while working towards a finished print. Aside from the 9 print editions we published over the years, we also worked together to create a large, varied body of mono-prints that pushed the limits of printmaking. We used all sorts of materials not traditionally found in prints, like velvet, sewing, felt, and at one point even a very large tobacco leaf.

2003 Radcliffe Bailey with Pam Paulson works in the studio on a large series of mono-prints.

Bailey’s work weaves together content from Black American history, African art, Jazz, vernacular art, and folktales, creating reverent yet celebratory images about his own personal journey as well as that of his ancestors. With his images, Bailey’s work encourages us to remember the past and the brave paths that so many people of color had to take and still have to make every day to be here now.

Radcliffe Bailey: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS, Color aquatint with color photocopy chine collé and velvet. 44 x 30” & 31 x 42”, Edition of 30